China. That one word summons up images of everything from faraway mystical lands, the Silk Road (original version), exotic foods and more. What it also does these days is bring to the fore thoughts of trade wars, tariffs, a technological giant and emerging superpower with the economic and military might to challenge the traditional global powers, at least in regional affairs if not truly on the international stage yet.

We’ve covered a quite a bit about Sino-US relations since President Trump came to power with a particular focus on how the current situation affects the technology world from a pricing and investment perspective. For this article, we look at the current situation and how we got here, as well as delving into some of the detail from a source discussing the possibility to decouple traditional tech from Chinese manufacturing. Finally, we take a look at some of the ramifications from both an investment and consumer perspective of the possible outcomes. For the juicy PC hardware gossip, do skip the following sections and scroll down to “The Source Discussion” section.

Primer – Recent Chinese Economic History

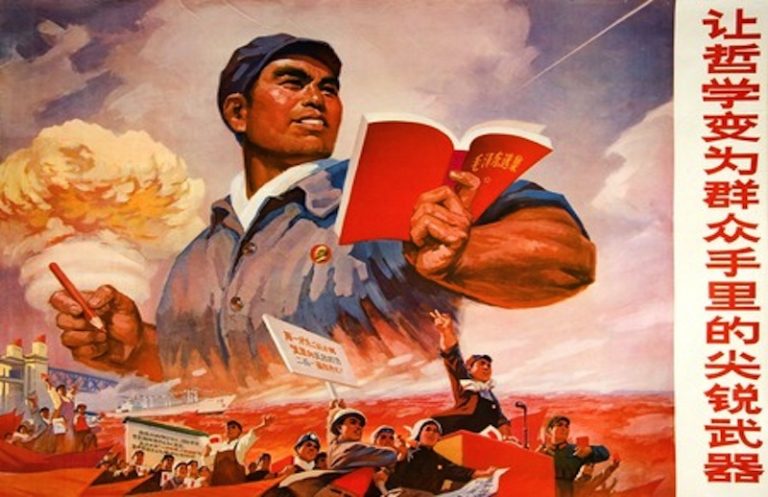

China, referred to even now as a communist country has had a vast amount of human capital at its disposal for a long time. However for much of its recent history has led a relatively isolated life economically with swathes of the country dedicated to farming and not much else. Following the 2nd world war, the Communist Party in China took significant advice from the former Soviet Union to help develop the economy into a centrally managed, socialist-style with the objective of improving efficiency via investment in heavy industry. Still significantly focussed on agriculture but in a more organised manner than had been previously.

In the late 1950’s to mid-1960’s however, China became frustrated by the lack of efficiency it saw as evidently brought about by the highly centralised command structure of the Soviet economic model and decided to go its own path, particularly after poorly planned water control infrastructure combined with poor weather culminated in an agricultural crisis which saw millions of people die from starvation. This ultimately led to decades of slow but steady reform to incorporate many of the modern mechanics of Western capitalism into the Chinese economy, albeit still with a heavy focus on central oversight if not absolute control.

During its period of significant self-discovery and adjustment, China remained apart from most of the global economic free-trade movement, probably for the best considering it was only in the 1980s that the government liberalised commodity pricing by allowing prices to be set via supply and demand rather than central decision. A crucial piece of legislation which paved the way to the efficient allocation of resources which most of the world now takes for granted.

I’m obviously glossing over huge amounts of history here, but the most important point to note was that this all led up to the liberalisation of the Chinese economy, culminating in its eventual ability to join the World Trade Organisation in 2001, a lengthy process which saw China first engage with regional trade organisations as its economy gradually opened up. WTO entry finally saw China allow a degree of foreign investment and a commitment to multilateral trade and the international rules based system of governance which in some ways has been under attack in recent years.

Even prior to WTO official entry, US-Sino trade had been gradually increasing as US and other international corporations sought access to China’s huge consumer base, however WTO entry was to secure the next generation of Chinese growth. With a commitment to multilateralism and ongoing foreign investment and trade of its own taking place, the world figured that it was time to take advantage of the extremely cheap labour in a relatively stable part of the world and subsequently foreign investment in China as well as domestic industry began driving huge levels of sustained economic growth which many have commented as being the largest and most consistent engine for global growth and the reduction of poverty with economic growth since the 90s generally being in the high single to low double digits territory year in, year out.

Outcome – Chinese Liberalisation

Of course, it’s relatively easy to drive economic growth when you are moving farmers whose economic output is counted in terms of bowls of rice they eat into cities to work in factories. A successful example of capitalist, economic trickle down (which generally works well in the early stages with varied results in later stages). However, as China has grown economically, it has also become more expensive to outsource to, coupled with the fact that the Chinese economy is still not as open as many would like.

“The undeniable truth is that the western world has come to rely on Chinese manufacturing and this is evident in the fact that over the last few decades”

What began as a trickle of raw material production for cheap has resulted in an avalanche of high-technology outsourcing since even though China is not as cheap as it once was, it’s still significantly cheaper to produce high technology there than it is in the west with higher and more expensive standards of living needing to be maintained by employees. From a corporate perspective, it was an absolute windfall. Outsource to China, costs go down, prices stay the same (or even creep up) and profit margins go up (or losses decrease). Outsourcing to a foreign land doesn’t come overnight of course. Relations need to be struck, commercial engagements agreed, contracts signed, facilities built, people hired and trained, supply chains committed to and more.

What this means inevitably is that a huge amount of western economic output is now tied to the outsourced model. While it’s relatively easy to move manufacturing of say fabric from China to Indonesia or other up and coming low-cost labour nations (note I said relatively easy, not easy), the technology industry has a bigger problem. Technology manufacturing requires significantly more training and supply chain management/integration than raw commodities and this is where we are now. Western companies, driven by the valid capitalistic model to seek out the most efficient means of production to compete with others and remain profitable have thrown every single virtual egg into the basket of outsourcing where costs can be cut over the last 30+ years. This is the kind of economic integration which doesn’t get unpicked overnight and indeed, even if it were to be attempted to begin to decouple, would those jobs be “onshored” back to the primary country of business? Unlikely, as our source will tell us later.

The Problems – Made in China 2025, Belt and Road Initiative

Much of the problem exists in the shape of the US feeling that China may be getting a bit too big for its boots. High profile plans such as “Made in China 2025” which aims to reduce China’s reliance on foreign technology with a shift to domestic technology along with the “Belt and Road Initiative” which is trying to make China the centre of trade for emerging economies, coupled with concerns over long term intellectual property transfer, the rise of Chinese technology on what some perceive as the result of that transfer, Chinese stockpiling of assets such as US sovereign debt and gold bullion, along with a significant trade imbalance have all led the US to the situation we’re in today.

To be clear, this is not a situation entirely of Trump’s making. Democrats and Republicans alike have both had long term concerns over American corporations doing business with China, particularly in sensitive areas such as technology and defence. China has embraced many of the hallmarks of western capitalism but retains sufficient independence from the rules the western world is used to which enables it to progress in a way that many see as unfair. Fairness is part of the issue but realistically it’s more like an “I’ll play fair when I have to but not when I won’t get caught” approach, all too evident in numerous US – European conflicts over Boeing and Airbus over the decades. State subsidisation of favoured or strategic companies has long been the modus operandi of every country/bloc in the world, in that sense China is no different from others.

Recent developments in the trade war have seen a cooling off from some of the fanfare China has touted in recent years including the news this week that Beijing no longer requires local governments to work explicitly towards the Made in China 2025 policy (source), although it is clear that the policy should still be implemented and that the drop of the name seems to be more about the show than the substance.

It’s also worth keeping in mind that China is not alone in the avenue it is pursuing. South Korea has its famous chaebols that were significantly favoured and had huge sums of money thrown at them to catch up with western competitors, decades of investment which culminated in the likes of Samsung now being the world’s largest chipmaker and its carmakers in many ways being the modern equivalents of Japanese carmakers in the 80s and 90s. The difference of course is that South Korea and Japan are about making money within a framework which is regarded as non-detrimental to US interests while China is increasingly regarded as a geopolitical competitor and/or threat.

The Source Discussion

I had the opportunity to ask some questions to a reasonable sized PC hardware assembler/manufacturer/retailer recently and this is what they had to say on the topic. Special thanks to Usman for getting me an industry source willing to talk on the topic. The source remains anonymous but I am convinced of their authenticity.

Wccftech: What is your view on the level of intellectual property transfer that is occurring between US and Chinese companies?

Source: Quite a bit of IP transfers from OEM to ODM. For our tooling projects, the ODM we select is responsible for taking our sketches and producing the image renderings. Then, after we provide our feedback on these they are responsible for prototype fabrication, modifications of design from our feedback, making all the tooling and then mass production. We lean quite heavily on Chinese ODMs in the design and development process and completely on them for the mass production.

W: Do you feel that private sector focus on making quarterly profits has made it misstep strategically with regards to gaining access to Chinese markets/manufacturers?

S: On the question of tariffs, I believe the electronics industry is too reliant on Chinese manufacturing because of the reduced labour cost and the availability of natural resources. Cheap items such as motherboards and peripherals are expected to remain in China since the cost to move the manufacturing is too high, even when factoring in tariff costs. Many Taiwan AICs are finding out that factory space is very limited and resources for building new factories non-existent in their homeland. As a result, most AICs are absorbing the tariff cost and passing on some or most of it to the consumer in subtle ways. Some have a clear advantage since they had existing manufacturing based in Taiwan which now allows them to have cost and sales advantage on NVIDIA RTX graphics cards sales in the US as the other AICs are impacted by the tariff but even those that do have quite limited manufacturing capacity in Taiwan so it’s only high end RTX graphics cards and not lower end GPUs or motherboards which will be able to avoid the tariffs.

AICs and other electronics OEMs are in a holding pattern right now since the 25% tariff isn’t in play yet and the possibility of trade agreements or the end of tariffs mean there is no incentive to expend the high investment right now to move manufacturing to other countries. Some are announcing plans to move some manufacturing out of China with Channel Well (large PSU manufacturer) planning a factory in Vietnam, while Quanta (Dell) and Foxconn (Apple) have plans to ramp up manufacturing in the US in the event that products are hit by tariffs

Memory is mostly unaffected by tariffs since large OEMs such as Micron and WD have existing manufacturing outside China, as do smaller firms like Avant.

W: Is there sufficient talent available in other economies to allow for a reasonably efficient on-shoring to take place regardless of the cost implications?

S: An AIC did express to me that moving manufacturing outside China or Taiwan wouldn’t be considered at this time given the lack of talent and presence and the uncertainty regarding the duration of the tariffs, they’ll aim to exhaust their options in Taiwan first before considering moving elsewhere, but it’s unlikely to go to the US and they’d look at places like Mexico, Malaysia, Singapore and Vietnam. It would also have to be quite clear that the tariffs were going to persist for a long time for the investment to be deemed worthwhile as they would have to relocate many personnel to do this too. The decision would be made in anything from a few months to a year but then the hard work would start and both the cost and effort to move would be enormous.

W: How difficult would it be for your company to continue operations in the current way if the US continues to impose restrictions on selling to Chinese companies it suspects of IP theft?

S: If the 10% tariffs increase to 25%, then we would have to raise prices to cover the costs but customers would not see a huge increase as we are sourcing inexpensive components and peripherals from China that do not make up a large percentage of the overall computer cost (things like motherboards, CPU coolers, PSU, fans, cases, keyboard and mouse). The expensive components such as CPU, RAM, SSD, some GPUs (depending on the AIC) and OS would generally not be hit. We would also explore setting up system integration in Mexico and import some of the components we buy from Chinese ODMs to Mexico in order to avoid some of the import tax.

Another factor which also increases reliance on Chinese manufacturing is the Made in China 17% tax credit provided by the Chinese government to its ODMs as long as they can show that payment was received from and the product was shipped to a country other than China, which provides a huge advantage over ODMs not in China.

If the unlisted items such as monitors, laptops and complete desktop systems were hit with a tariff then the impact would be much greater as prices would certainly rise on these products. Companies like Dell and Apple that do business with tier 1 ODMs like Quanta and Foxconn which have the capability of ramping up US manufacturing may gain a cost advantage. If either of these two scenarios were to occur, we would start attending many more trade shows in search of ODMs with factories outside of China to avoid paying the tax.

The Decouple Detail

So what would we be looking at if indeed there was to be a serious attempt to reduce western technological reliance on China?

Well the first major problem that needs to be overcome is that China is the world’s largest rare earth producer. According to mining-technology.com, China produced 100,000 tonnes of the stuff in 2013, accounting for more than 90% of global production and given it is the manufacturing plant for global technology, unsurprisingly consumed 60% of global supply itself immediately. Estimates put its reserves at being approximately 40% of global total reserves. In a genuine shift away from China, Brazil probably stands to gain the most in that it has approximately 20% of rare earth reserves, although its 2013 production was a paltry 140 tonnes so clearly huge infrastructure investment would be needed to tap into those reserves.

Much like the oil problem, the lack of oil is not really a problem for the world, the lack of cheap oil is the real economic issue. Digging a well in the Middle East is significantly cheaper than fracking or extraction from Canadian oil sands and it remains to be seen how cheaply rare earths could be extracted in sufficient volume from countries other than China but in all likelihood it would take years if not decades and demand billions in investment. Those costs would obviously be significantly amortised across production but it’s still a cost which puts the end price of the phone in your pocket or the graphics card in your PC up assuming that China acts to protect its interests if its technology industries are threatened.

“If other locations can supply sufficient rare earths at an appropriate price level to compete, the global supply chain logistics need to shift to compensate for this. Brazil would seem to indicate a move towards Mexican production, meaning NAFTA or whatever future equivalent for it exists becomes more important.”

Transport links between Brazil and Mexico would need to be beefed up and criminality in both countries reined in significantly to prevent security costs rising too high.

Once that is done, factories need to be built, relocation packages agreed (because let’s be honest, as we covered here it would still be predominantly Chinese companies that have the expertise to get these new locations up and running relatively quickly), visas applied for and granted, local talent hired and more importantly trained, export controls negotiated and global shipping planned. Emissions legislation investigated and manufacturing processes refined to adhere to new environmental protection laws. This amounts to a huge investment in sunk costs, additionally corporations may have to take massive hits on the book value of Chinese infrastructure, selling or repurposing it towards different use.

None of this comes cheaply of course, the costs for lawyers, accountants and regulatory specialists alone will dominate budgets and much like the finance industry in the wake of the 2007-08 crisis, massive investment will need to be sunk into adhering to a differing rule regime with those costs coming straight out of the bottom line and contributing nothing to increasing revenue. It makes for grim reading.

Ultimately, these costs will need to be amortised and absorbed or passed on. Some companies will no doubt die off and others will come to the fore but one thing is for sure: 3 decades of tying global technological manufacturing and expertise to one country will take a concerted effort of at least years and possibly tens of years to unpick. That kind of investment is unlikely to come about if there is even a hint of uncertainty over the political will to pursue the kind of punitive trade relationship the US seems to be intent on with China. Even with as hard-nosed a President as Trump in the White House, a single term would likely bring about a more staid approach to international trade than is currently the case.

What is important to keep in mind however is that it’s not like all of these costs will come barrelling towards consumers at once. Incremental increases over time will be used as costs of transfer will ramp up and it’s likely instead that inflation on tech products will creep up over time. What does this mean? Well, it’s important to keep in mind that one of the goals of central banks is price stability with a generally accepted goal of approximately 2% inflation being “good”. It’s also important to keep in mind that different countries will weigh technology products differently but in general, the pressure on prices and potentially wages in that case will be upwards in nature. Central banks may use this period to increase interest rates further in an attempt to keep a lid on inflation although it could be written off as a once off cost increase (over a prolonged period however) of the cost of shifting away from Chinese manufacturing, much like inflation in the UK spiking post-Brexit and the weakening of the pound has also not directly resulted in a tightening of monetary policy.

The End Result

Capitalism has a lot of flaws in it, however its use is as widespread as it is primarily because it is the single best wealth creation engine that we know of. Does it create inequity? Absolutely. Will some people scramble their way to the top of the heap while others are unable to get onto the bottom but one rung of the ladder? Completely. Will capital allocation be inefficient in places? You bet. The thing is, there’s no better model for bringing wealth to the world and bringing wealth to the world is what furthers our advancement as a species as well as prevents some wars, famines and other nasty things that we could do without.

Inefficient capital allocation has absolutely been a problem for the technology industry when you look at the huge amounts of offshore profits held by (largely technology) corporations in tax havens doing nothing other than not being taxed. But although this has been a glaring inefficiency of the industry in the past, there is much that it has done right and the lowering of costs of production is an important factor in the value chain towards competitive pricing and giving consumers the best bang for their buck. In this sense, capital allocation has been absolutely efficient in that it has sought out the cheapest reliable means of producing high technology products and for the last 3 decades, this has been China.

Governments exist however to (among other things) make sure that the inefficiencies such as tendencies towards monopolies are ironed out (or at the very least managed) and that the strategic direction which takes account of things other than quarterly earnings cycles are taken into consideration. Sometimes it gets it right, sometimes not, but either way one thing is clear. If you have a significant portion of an economy (which has found the cheapest and most efficient means of production it can), is forced to move away from that, it will cost money and time and will ultimately mean that profit margins are eaten into, consumers pay higher prices or some combination of the two.

“From an investor perspective? It should be obvious to anyone with a vague interest in the markets that the rumbling trade war between the US and China is the key driver of global economic jitters these days.”

If the impasse is not genuinely resolved with more than lip service it’s hard to see anything other than the beginnings of a downturn. Indeed, many markets are already in correction territory for the year and tech stocks have borne a large part of the brunt given the significant exposure the industry has should a genuine US China trade crisis emerge. The problem is, if that happens then realistically, technology stocks won’t matter and the general rotation out of equities and into bonds will become widespread. In this event, expect equities to drop with technology stocks suffering disproportionately more than other stocks.

In a worst case scenario, the prospect of stagflation becomes a possibility with a trade war and protectionist global policies leading to a period of recession, high unemployment and high inflation as onshoring and other protectionist policies bite into the cost of production. Our best hope for reasonably priced graphics cards? As ever, it remains competition, free market mechanics and a settling of trade disagreements in a sensible way. Sometimes the carrot works, China has been given the carrot for decades and President Trump clearly thinks it’s time to use the stick.