After days of intermittent blackouts at the order of the Zimbabwe’s Minister of State for National Security, ISPs have restored connectivity through a judicial order issued Monday.

The cyber-affair adds Zimbabwe to a growing list of African countries—including Cameroon, Congo, and Ethiopia—whose governments have restricted internet expression in recent years.

The debacle demonstrates how easily internet access—a baseline for all tech ecosystems—can be taken away at the hands of the state.

It also provides another case study for techies and ISPs regaining their cyber rights. Internet and social media are back up in Zimbabwe — at least for now.

Protests lead to blackout

Similar to net shutdowns around the continent, politics and protests were the catalyst. Shortly after the government announced a dramatic increase in fuel prices on January 12, Zimbabwe’s Congress of Trade Unions called for a national strike.

Web and app blackouts in the Southern African country followed demonstrations that broke out in several cities. A government crackdown ensued with deaths reported.

“That began Monday [January 14]. A few demonstrations around the country become violent…Then on Tuesday morning there was a block on social media: Facebook, Twitter, and WhatsApp,” TechZim CEO Tinashe Nyahasha told TechCrunch on a call from Harare.

On January 15, Zimbabwe’s largest mobile carrier Econet Wireless confirmed via SMS and a message from founder Strive Masiyiwa that it had complied with a directive from the Minister of State for National Security to shutdown internet.

Net access was restored, taken down again, then restored, but social media sites remained blocked through January 21.

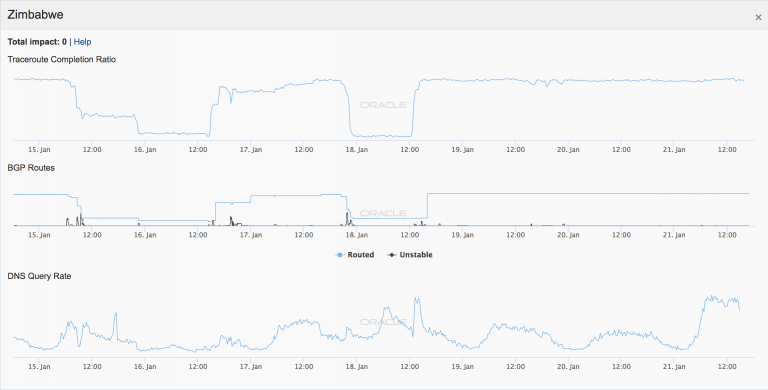

Data provided to TechCrunch from Oracle’s Internet Intelligence research unit confirm the net blackouts on January 16 and 18.

VPNs, government response

Throughout the restrictions, many of Zimbabwe’s citizens and techies resorted to VPNs and workarounds to access net and social media, according to Nyahasha.

Throughout the interruption TechZim ran updated stories on ways to bypass the cyber restrictions.

The Zimbabwean government’s response to the net shutdown started with denial—one minister referred to it as a congestion problem on local TV—to presidential spokesperson George Charamba invoking its necessity for national security reasons.

Then President Dambudzo Mnangawa took to Twitter to announce he would skip Davos meetings and return home to address the country’s unrest—a move panned online given his government’s restrictions on citizens using social media.

The Embassy of Zimbabwe in Washington, DC and Ministry for ICT did not respond to TechCrunch inquiries on the country’s internet and app restrictions.

Court ruling, takeaways

On Monday this week, Zimbabwe’s high court ordered an end to any net restrictions, ruling only the country’s president, not the National Security Minister, could legally block the internet. Econet’s Zimbabwe Chief of Staff Lovemore Nyatsine and sources on the ground confirmed to TechCrunch that net and app access were back up Tuesday.

Zimbabwe’s internet debacle created yet another obstacle for the country’s tech scene. The 2018 departure of 37–year President Robert Mugabe—a hero to some and progress impeding dictator to others—sparked hope for the lifting of long-time economic sanctions on Zimbabwe and optimism for its startup scene.

Some of that has been dashed by subsequent political instability and worsening economic conditions since Mugabe’s departure, but not all of it, according to TechZim CEO Tinashe Nyahasha.

“There was momentum and talk of people coming home and investing seed money. That’s slowed down…but that momentum is still there. It’s just not as fast as it could have been if the government had lived up to the expectations,” he said.

Of the current macro-environment for Zimbabwe’s tech sector, “The truth is, it’s bad but it has been much worse,” Tinashe said

With calls for continued protests, Monday’s court ruling is likely not the last word on the internet face-off between the government and Zimbabwe’s ISPs and tech community.

Per the ruling, a decision to restrict net or apps will have to come directly from Zimbabwe’s president, who will weigh the pros and cons.

On a case by case basis, African governments may see the economic and reputational costs of internet shutdowns are exceeding whatever benefits they seek to achieve.

Cameroon’s 2017 shutdown, covered here by TechCrunch, cost businesses millions and spurred international condemnation when local activists created a #BringBackOurInternet campaign that ultimately succeeded.

In the case of Zimbabwe, global internet rights group Access Now sprung to action, attaching its #KeepItOn hashtag to calls for the country’s government to reopen cyberspace soon after digital interference began.

Further attempts to restrict net and app access in Zimbabwe will likely revive what’s become a somewhat ironic cycle for cyber shutdowns. When governments cut off internet and social media access, citizens still find ways to use internet and social media to stop them.